Accounting for Learning Environments in Academic Screening

Read Full Research

A new study led by Rutgers researchers Dr. Adam Lekwa and Dr. Linda Reddy offers a striking takeaway: students’ risk scores on fall academic screeners can be misleading depending on the quality of classroom instruction that follows.

The team analyzed fall reading and math screening scores from more than 1,500 third graders and linked them to spring state test results, while also observing 72 teachers’ instructional practices. Their goal was to see whether teaching quality changed how well early test scores predicted end-of-year performance.

What they found:

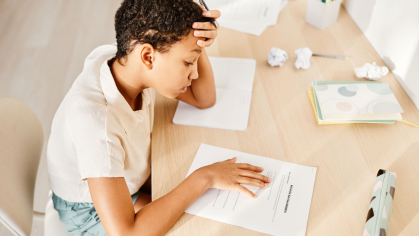

Screening scores did not predict outcomes equally across classrooms. In reading especially, students with identical fall scores had very different spring results depending on how effectively their teachers used evidence-based instructional strategies. Classrooms with weaker instructional practices produced more “false positives”—students flagged as needing intervention who ultimately met grade-level standards.

“Teaching matters—even for how we interpret data that’s supposed to be objective,” Dr. Lekwa noted.

Why it matters for everyday life:

Schools commonly use screeners to assign children to extra reading or math support. This study shows that a student may be labeled “at risk” not because of their ability, but because of the classroom environment they happen to be in. That misclassification can lead to unnecessary interventions, lost instructional time, and strain on school resources.

What’s new:

This is the first empirical evidence that the validity of academic screening tools depends on teaching quality. The practical implication: schools should use screening data to evaluate and strengthen instruction—not just to sort students into tiers.

(CoPilot, November 23, 2025)